China, Europe, United Kingdom, United States: Green regulations to tackle climate change in the building industry

Design and construction regulations that improve the energy efficiency of buildings are crucial to limit global warming to 1.5°C before the end of the century, but the regulatory landscape can be very complex and at times, it can be difficult to understand whether current regulations go far enough to meet national pledges for reaching net zero this century. In this article, we look at some of the regulations that have been promised by governments in China, across Europe, and the United States, and make an attempt to unravel how ambitious they really are.

Where does China stand?

As the largest global emitter of CO2, China, which has pledged to reach peak emissions by 2030 and achieve net zero by 2060, is an interesting case study. According to the Green Buildings Performance Network (GBPN), a global organization which provides policy expertise and technical assistance to advance building energy performance, China has been “actively promoting building energy efficiency with an increasing concern for sustainable development, national energy security, and a growing interest in pursuing a low-carbon economy” since the 1980s, with the first “national building energy code for new residential buildings in cold and severe cold regions” adopted as far back as 1986.[1]

But given China’s unprecedented economic growth since then, how effective have these regulations and building codes truly been? From 1995 to 2005, China’s building stock nearly tripled, and the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics estimates that in recent years, the rate of growth has been equal to some 4bn m² of new buildings constructed every year[2]. Given this frantic rate of growth, the GBPN states that: “China’s central and local governments have recognized the urgent need to improve building energy efficiency, through the adoption of both regulatory policies (i.e., building codes) and market-based and financial policies (i.e., building energy labels and incentives)”, but the latter remains on a voluntary basis.

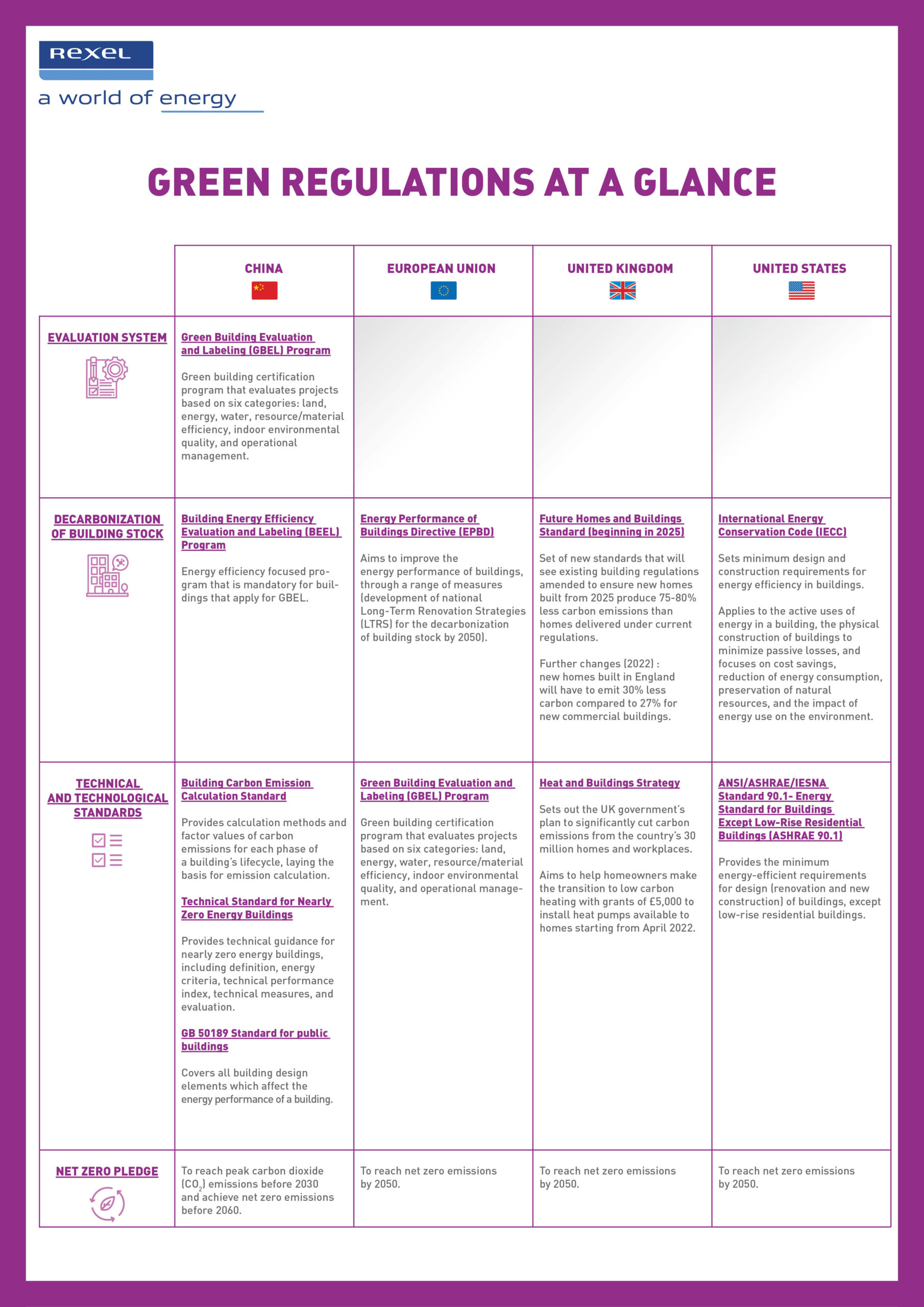

Currently, there are two energy-labeling programs: the Green Building Evaluation and Labeling (GBEL) Program and the Building Energy Efficiency Evaluation and Labeling (BEEL) Program, in addition to a Building Carbon Emission Calculation Standard and a Technical Standard for Nearly Zero Energy Buildings. In 2015, GB 50189 a design standard for the energy efficiency of public buildings, was also introduced to improve efficiency in new construction, expansion, and renovation of public buildings[3]. There are also incentives to build sustainably with subsidies available for the construction of ultra-low energy buildings and for integrating renewable energy into buildings. Nevertheless, Wei Yang and Jie Li, researchers at Tianjin University’s School of Architecture in Tianjin (North East China)[4], argue that “stricter building energy saving targets and standards are needed and a life cycle approach should be applied”. They also suggest that in addition to the need for vast amounts of investment to ensure the sustainability of existing as well as new buildings, the amount of new construction would need to be restricted.

With buildings and the built environment currently contributing about half of the country’s total CO2 emissions and the heating and operation of buildings accounting for about 22% of national energy-related emissions, a lot of work remains to enforce and strengthen current and future regulations and reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

What approach is Europe taking?

Looking towards Europe, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) is the cornerstone of the EU’s building energy regulations. Together with relevant provisions in the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) and the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), the EPBD is the EU’s “main legislative instrument aiming to promote the improvement of the energy performance of buildings within the Community”.[5]

The EPBD, which concerns both new and existing building stock, was first adopted in 2010, revised in 2018, and was updated once again as recently as December 2021 to align it with the Paris Agreement goal of reaching net zero by 2050. It is part of the Renovation Wave initiative of the European Green Deal, which aims to decarbonize Europe’s buildings whilst tackling fuel poverty and driving economic growth. Among other policies, it includes the “development of national Long-Term Renovation Strategies (LTRS) for the decarbonization of building stock by 2050, setting minimum performance requirements at cost-optimal levels for buildings undergoing major renovation and meeting the Nearly-Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB) criteria for all new buildings as of 2021. The EPBD also prescribes the issuance of Energy Performance Certificates (EPC) every time a building is sold or rented”.[6]

Among the most recent updates to the Directive is the inclusion of mandatory energy efficiency upgrades for public and non-residential buildings to at least EPC Band F by 2027 and to Band E by 2030. Residential building will need to have a minimum EPC rating of Band E by 2033. The Directive also supports ending incentives for fossil fuel boilers later this decade although it doesn’t go as far as actually banning them.[7]

The upgrade of existing building stock has been the most contentious issue and there has been some debate around how far these plans should go without infringing on the powers of national governments. Whatever happens in the near future, one thing is clear, with 85% of EU buildings constructed before 2001 and the vast majority expected to be still standing in 2050, any overhaul of the EU’s existing building stock will be a giant task and more detailed plans are needed on a regional as well as a national level to ensure the region reaches carbon neutrality in less than three decades.

Looking to the UK, which officially left the European Union in early 2021, the Future Homes and Buildings Standard, announced in the spring of 2019 and due to pass into law in 2025, builds on the existing Building Regulations for new homes, and aims to reduce carbon emissions by 75-80% compared to homes built under current standards. Although the full details of the new regulations aren’t yet known, they will include things like mandatory space for hot water storage, a ban on combi boilers, the requirement for heating systems to run at lower temperatures, enabling heat pumps to work effectively, and significant improvements to insulation and airtightness.[8] Paving the way to the new standard, changes in existing regulations this year will mean that from June, new homes in England will have to produce 30% less carbon emissions, and new commercial buildings will have to cut emissions by 27%.

However, although the regulations apply to all new homes, existing homes will only need to adhere to some of the standards when making significant improvements. In addition, major carbon reduction and heat saving upgrades such as the long-mooted replacement of gas boilers, has not been made mandatory. In the UK government’s recently published Heat and Building Strategy document, the legislative ban on their sale has been replaced with an “ambition to phase out the installation of natural gas boilers beyond 2035”[9]. The UK government plans to do this by financially incentivizing households to adopt low carbon alternatives such as heat pumps, with £5,000 promised per household starting from April 2022.

The UK’s Green Building Council has challenged the Heat and Building Strategy, saying that it doesn’t go far enough to fully decarbonize buildings and change the way they are heated over the next 30 years. Although existing regulations and financial commitments for both the retrofit of existing homes as well as new builds are encouraging, much more investment and legislation is needed to secure the low carbon transition that the UK’s building stock needs to meet the country’s net zero commitments.

How does the US compare?

In the US, where buildings account for 39% of energy use and two-thirds of electricity[10], the national government does not have authority to pass mandatory building codes. However, states and local governments can choose to adopt one of the national model energy codes.[11] These codes set minimum requirements for the energy-efficient design and construction of new buildings as well as for renovations. They also relate to the energy use of the building as well as their lifetime emissions.

In addition to more generic building codes for commercial and residential buildings, there are two main national model building codes which look specifically at the energy consumption of buildings: the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and the ANSI/ASHRAE/IESNA Standard 90.1- Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings (ASHRAE 90.1). The IECC takes into account the energy efficiency of a building based on several factors including cost, energy usage, the use of natural resources, and the impact of energy use on the environment, and has been adopted by most states and municipal governments in the United States. It is updated every three years to incorporate new building technologies and practices as they evolve over time and sets minimum efficiency standards for new construction relating to a structure’s walls, floors, ceilings, lighting, windows, doors, duct leakage, and air leakage. ASHRAE 90.1 which is updated regularly, most recently in 2019, to take account of newer, more efficient technologies, provides minimum requirements for energy-efficient designs for buildings, in particular government and commercial buildings when they are being constructed or renovated. Most states have applied the standard to their commercial buildings and some to their government buildings.

Do building regulations go far enough?

Building energy codes and regulations are only effective if they’re enforced, which can be very challenging, with few jurisdictions issuing fines for non-compliance. However, their adoption can be advanced in other ways, with many countries supplementing their regulatory framework for building design and construction with financial incentives, from subsidies and grants to low-interest loans and tax incentives.

Global emissions from building operations hit their highest level in history in 2019, increasing to 9.95 GtCO2 that year and accounting for 38% of all energy-related CO2 emissions when adding building construction industry emissions.[12] The IEA states that several factors have contributed to this rise, including growing energy demand for heating and cooling with rising air-conditioner ownership and extreme weather events.

But as the world slowly continues to recover in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, promises made by national governments to build back better are also being seen as an opportunity “to reshape the built environment to advance the clean energy transition and avoid locking in inefficient and high-emitting technologies”.[13]

The opportunities for a global clean energy transition for the world’s existing and future building stock are at our fingertips, but firm local, national, regional, and global commitments and the regulations and policies to uphold and advocate for them are needed. Only time will tell if, when it comes to our buildings, we can remain on track to slow climate change, reduce fuel poverty, and drive economic recovery through the design and construction of an energy-efficient and net zero built environment.

[1] https://www.gbpn.org/activities/china/

[2] https://www.eceee.org/library/conference_proceedings/eceee_Summer_Studies/2019/3-policy-and-governance/building-energy-efficiency-policy-in-chinese-cities-and-comparison-with-international-cities/

[3] https://www.iea.org/policies/7920-gb-50189-2015-design-standard-for-energy-efficiency-of-public-buildings

[4] https://www.buildingsandcities.org/insights/commentaries/cop26-china.html

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directive_on_the_energy_performance_of_buildings

[6] https://caneurope.org/revision-energy-performance-buildings-directive/

[7] EPBD revisions stop short of backing EU-wide fossil fuel boiler ban – Heating and Ventilation News (hvnplus.co.uk)

[8] https://www.homebuilding.co.uk/advice/future-homes-standard

[9]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1036226/E02666137_CP_388_Heat_and_Buildings_Accessible.pdf

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_energy_building_codes

[11] https://www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/articles/energy-codes-101-what-are-they-and-what-does-role

[12] https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/building-sector-emissions-hit-record-high-low-carbon-pandemic

[13] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-covid-19-crisis-and-clean-energy-progress/buildings#abstract