Sustainable bonds, a driver for the energy transition?

Meeting at the end of 2021 in Glasgow as part of COP26, the participating states and NGOs confirmed the decisive importance of the fight against global warming in their environmental policies, followed by companies that, in increasing numbers, integrate ambitious sustainability criteria into their strategies.

This is particularly evident in their interest in financing arrangements related to sustainable development.

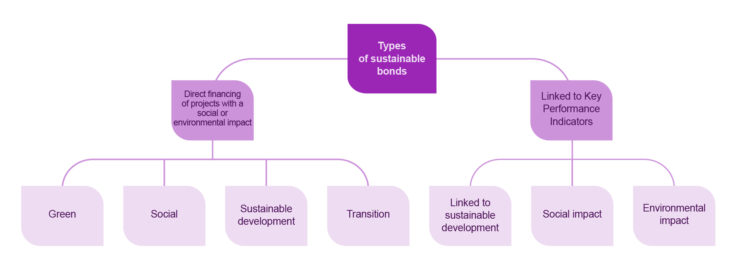

The different types of sustainable bonds

There are different types of sustainable bonds, a generic term encompassing schemes with different operations and objectives. Some may finance a specific project with an environmental or social purpose. This category includes, but is not limited to, “green bonds”, “blue bonds”, “climate bonds”, and “social bonds”.

Sustainable bonds also include those that are linked to Key Performance Indicators (KPI). These are mainly Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLB), but also social and environmental impact bonds. Their specificity is to link their remuneration to the achievement of sustainable development objectives defined by the issuer but validated or even co-constructed with independent third-party experts. As a sign of its commitment, the company agrees to pay a higher coupon if it fails to meet its commitments. In other words, these bonds are indexed to the company’s achievement of its commitments to reduce its environmental or social impact.

In terms of amounts raised, green bond issues are leading the way: Globally, they accounted for €300 billion in 2020 and nearly €440 billion in 2021[1], i.e. half of all sustainable bonds. To illustrate this craze, another figure is significant: The European Commission’s first green bond, launched in October 2021 under the name NextGenerationEU, received more than €135 billion in applications, raising €12 billion[2],! This success should not make us forget bonds with a social vocation, with the European Union (EU) also leading the way with its “SURE” program[3], intended to finance measures to resolve or reduce unemployment linked to the pandemic.

Expanding regulatory framework

Although green bonds first appeared in 2007 with the first issue by the European Investment Bank (EIB), it was not until 2014, with the publication of the Green Bond Principles (GBP) by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), that a structured framework promoting transparency on the use of the funds raised appeared. Since 2015, France has had its own label[4] and the European Union has established a framework for reporting, monitoring, and evaluation mechanisms by the European Commission and independent auditors for green investments made. It has also created a green taxonomy, which establishes an emission threshold below which a company can be considered “green”.

On this basis, the European Commission has defined a European Green Bond Standard (or EUGBS)[5]. These regulations are all the more important as sustainable bonds still suffer from the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes a green or social project, even though the profile of issuers is diversifying and broadening.

As for SLBs, their operation is specific in that they are not attached to a dedicated sustainability project, but their issuer commits to achieving overall key environmental, social, or governance (ESG) performance indicators. This gives the issuer full freedom to choose how it will achieve its sustainable development objectives, especially as there are no standardized parameters at international level. Their growing success shows that they meet the need for companies to commit to a low-carbon economy by acting comprehensively on all the parameters of their activity.

Issuers increasingly linked to companies

Sustainable bonds can be issued by all types of actors. Initially issued by international public actors, sustainable bonds are increasingly of interest to companies, particularly in the banking and energy sectors. Engie has become the largest private issuer of green bonds with a €1.5 billion issue in October 2021, bringing its total bond holdings to over €14 billion. The objective: Financing its energy transition plan, which provides for increased use of renewable energies, green hydrogen storage, decarbonized distribution, and energy efficiency, with the ultimate goal of achieving carbon neutrality.

EDF is also developing an active policy in this area, which began in 2013 to develop its wind and solar projects, then its hydroelectric infrastructures, before extending its fundraising missions to energy efficiency and biodiversity.

Rexel issued SLBs for a total amount of €1 billion in 2021[6]. In this context, the company has defined two KPIs aligned with its 2030 climate objectives and is committed to: A 23% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions related to the consumption of products sold, per euro of turnover (scope 3)[7] by December 31, 2023 (compared to 2016), and a 23.7% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions related to energy consumption in its operations (scopes 1 and 2) by December 31, 2023 (compared to 2016). The issue was carried out in compliance with the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (SLPB) published by the ICMA, and reviewed by Vigeo Eiris, which issued an opinion as an independent third-party expert.

Increasingly broad objectives but better controlled commitments

These bonds are largely subscribed via ESG-oriented funds, as investors have become very keen on eco-responsible investments, to the point of accepting a reduction in their remuneration in return for environmental or social commitments (a premium appropriately called “Greenium”). Green and social finance is thus a powerful driver for companies, which find abundant financial resources to finance their energy transition and, more broadly, their ESG policy. The movement should continue while expanding and structuring itself with a professionalization and standardization of the market.

Today, we are seeing a diversification of targets for sustainable bonds: Bonds linked to the preservation of the oceans (known as “blue bonds”), bonds linked to one or more of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the 2030 Agenda[8]. This multiplication of objectives and the greater diversity of issuers may raise concerns about the reliability of the projects and the quality of those who initiate them. In this context, in order to reassure investors, the intervention of an independent external auditor certifying the alignment of the issue with the Green & Social Bond Principles should become systematic in the years to come. For SLBs, KPIs should also become more standardized to facilitate comparisons and checks on the commitments made.

While the bulk of the energy transition remains to be accomplished, and the goal of limiting the increase in the earth’s temperature to 1.5 degrees seems to be become more and more difficult to achieve, sustainable bonds are a promising source of financing to accelerate the decarbonization of growth. Invented and developed in Europe, they are now spreading to other parts of the world.

Questions for Jean-François Deiss, VP Financing and Treasury at Rexel

- In two sentences, how would you define a sustainable bond?

For Rexel, and given the Group’s activity and its financing needs, a sustainable bond is a bond whose benefit (coupon) is related to the achievement of goals linked to greenhouse gas emissions reductions, but whose proceeds can be reallocated to Rexel’s daily activity. If the set goals are not reached, this coupon will be more expensive. There are other categories for sustainable bonds, such as green bonds, which allow financing of specific projects, but these are not compatible with Rexel’s activity.

- What types of investors are being targeted?

Our priority targets are investors dedicated to sustainable investments, a market segment that is growing rapidly. However, more traditional investors are equally interested in owning “sustainable” products in their portfolios.

- Are there any organizations that help you with this?

For any new bond issue, relevant criteria and goals have to be discussed and validated by an independent expert. In Rexel’s case, we have been working with Vigeo Eiris. This support has allowed us to publish the framework of Rexel’s sustainable approach and the rating awarded by Vigeo Eiris on our website. To find more detailed information on this topic, you can visit our rexel.com website.

- Who certifies that the objectives have been achieved?

The achievement of bonds objectives is certified by an independent third-party body, in our case the firm PWC.

- Will this type of operation be repeated?

I think this form of “sustainable” financing is bound to develop significantly in the coming years, and that, in the long run, it will become a discriminating asset in the sense that sustainable bond issuers will undoubtedly have a greater advantage in terms of price (greenium) than other issuers. As a consequence, we would like to continue on this path for upcoming bond issues.

[2] EU issues record-breaking green bonds (actu-environnement.com)

[3] European Commission issues first emission of EU SURE social bonds (europa.eu)

[4] The Greenfin label | Ministry of Ecological Transition (ecologie.gouv.fr)

[5] Questions and Answers: European Green Bonds Regulation (europa.eu)

[6] https://www.rexel.com/en/medias/news/with-the-successful-placement-of-its-new-sustainability-linked-notes-offering-all-of-rexels-outstanding-bonds-are-now-linked-to-ghg-emission-reduction-targets/

[7] https://www.sami.eco/post/scopes-1-2-3-emissions-definition

https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/scope-1-and-scope-2-inventory-guidance + https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/scope-3-inventory-guidance

[8] Agenda 2030 in France – The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) website (agenda-2030.fr)